Understanding the Accounting Equation

The accounting equation is a fundamental concept that underpins the practice of accounting and forms the backbone of all double-entry bookkeeping systems. This key principle ensures that every financial transaction affects at least two accounts and that the company’s financial statements always remain balanced. By grasping the structure and logic of the accounting equation, individuals gain valuable insights into how businesses track their financial status and maintain accuracy in their records. On this page, we delve into the components, importance, and practical applications of the accounting equation, guiding you through its various elements for a thorough and accessible understanding.

Maintaining Equilibrium with Double-Entry Accounting

Double-entry accounting is the practical methodology derived from the accounting equation. For every financial transaction, there must be corresponding entries that keep the equation balanced: any addition or subtraction from one side must be matched by a corresponding change on the other side. This ensures that the sum of assets is always equal to the sum of liabilities and owner’s equity. Through this method, errors are minimized, transparency is maximized, and the overall integrity of financial records is maintained, making it a cornerstone of modern accounting practice.

The Role of Journals and Ledgers in Balance

Journals and ledgers constitute the tools accountants use to record and summarize each transaction’s dual impact on the accounting equation. Every entry in a journal is posted to the appropriate ledger accounts, directly affecting the balance of assets, liabilities, or equity. This systematic approach guarantees that the balance prescribed by the accounting equation is monitored continuously. If an entry were to go unbalanced, it would immediately become evident in the ledgers, prompting investigation and correction. The process fosters accountability and guards against misstatement in financial reporting.

Impact on Financial Statements

Financial statements—the balance sheet, income statement, and statement of owner’s equity—derive their reliability from the accounting equation. The balance sheet, for instance, is a representation of the equation at a particular point in time, showing precisely how assets, liabilities, and equity align. If the equation fails to balance on the financial statements, it indicates errors that require resolution. This direct link ensures that the financial position presented is both accurate and verifiable, enabling stakeholders to trust the numbers they see.

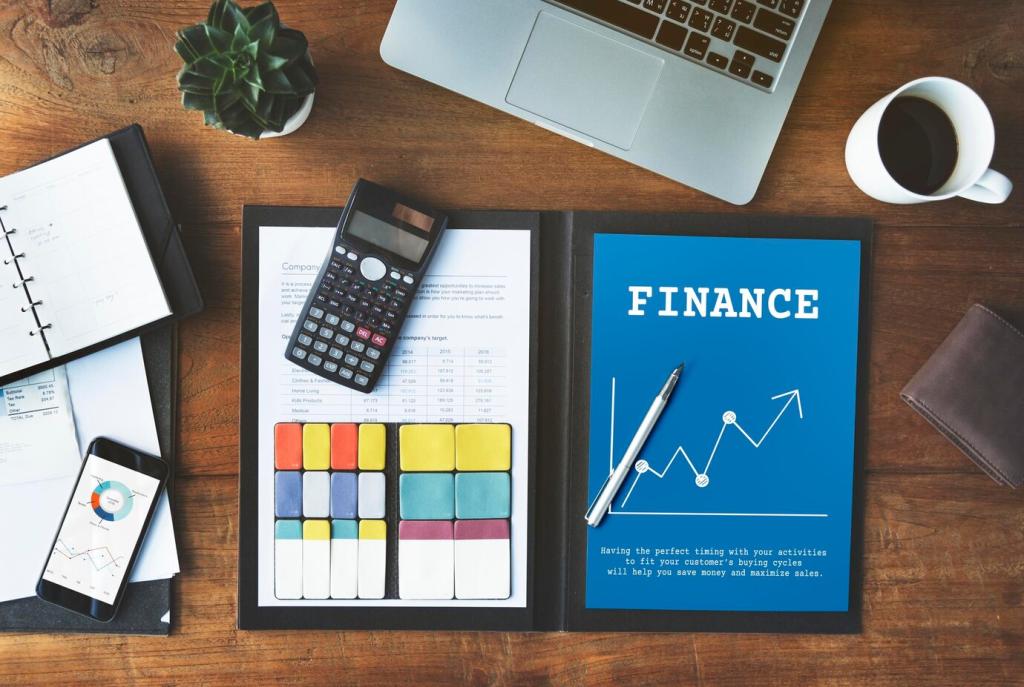

Decision-Making and Strategy

Managers and business owners use the insights provided by the accounting equation to inform key strategic decisions, such as expanding operations, seeking loans, or distributing profits. With a clear understanding of how each proposed move would alter assets, liabilities, or equity, decision-makers can forecast the impact on the company’s financial health. This foresight enables more prudent planning and risk management, which are vital for long-term success and sustainable growth.

Legal and Regulatory Compliance

Regulatory bodies and tax authorities rely on accurate financial records based on the accounting equation to ensure companies meet their legal obligations. This includes tax filings, financial disclosures, and meeting the requirements of lenders or investors. By maintaining the equation in all records, businesses demonstrate their adherence to regulatory standards and reduce their exposure to legal risks or penalties. Compliance not only preserves reputation but also opens doors to new opportunities by fostering trust with external parties.

The Equation in Different Business Structures

In sole proprietorships, the accounting equation directly connects business finances to the owner’s personal finances. There is no legal distinction between the business and the owner, meaning assets and liabilities are often closely intertwined. Changes in owner’s equity arise from personal contributions, withdrawals, and the business’s profits or losses. This straightforward relationship means any movement in one part of the equation has an immediate and understandable effect on the owner’s net worth, making financial tracking more transparent but also more personally impactful.

How Transactions Affect the Equation

When a company purchases inventory using cash, both assets decrease (cash) and increase (inventory), leaving the overall asset value unchanged but altering its composition. Conversely, taking out a loan increases both the assets (cash received) and liabilities (the new loan obligation), resulting in a larger balance sheet but in a still-balanced equation. Accurately recording these transactions prevents errors and maintains the trustworthiness of financial statements, illustrating the ongoing interplay between different categories.

The Equation and Financial Analysis

Liquidity, the company’s ability to meet short-term obligations, and solvency, its capacity to satisfy long-term debts, are directly tied to the balances reflected in the accounting equation. Analysts review the relationship between current assets and liabilities to gauge liquidity, while the overall structure of the equation informs solvency analysis. A well-balanced equation featuring adequate asset levels relative to liabilities shows that the business can honor its commitments, thereby boosting confidence among creditors and investors.

Confusing Profit with Cash Flow

Many people mistakenly equate profits with increases in cash, but the accounting equation distinguishes between earnings recorded and actual cash movements. Revenue earned may not be collected immediately, and expenses incurred can be deferred, impacting assets and liabilities differently. By failing to recognize this distinction, business owners may overestimate their liquidity and make poor financial decisions, highlighting the necessity of respecting the equation’s logic in every analysis.

Ignoring Non-Cash Transactions

Non-cash activities, such as depreciation or issuing shares, don’t always involve a physical exchange of cash but they significantly affect the accounting equation. Depreciation reduces asset values and equity over time, while issuing shares increases equity and possibly brings in cash or other assets. Omitting these non-cash movements leads to incomplete financial records and a false picture of the business’s standing. Comprehensive accounting requires that every transaction, cash or not, is properly identified and integrated into the equation.

Overlooking Adjustments and Accruals

At the end of each accounting period, adjustments and accruals ensure the financial records accurately reflect the company’s obligations and achievements. These entries, such as accrued expenses or unearned revenue, update the balance of assets, liabilities, and equity, even though the cash may not yet be exchanged. Omitting such entries results in the accounting equation being unbalanced and misleads both internal and external users. Precisely recording all accruals and adjustments is a crucial discipline for fair and lawful accounting.